Before the white man’s game of cricket reached our villages, our boys already played the games of their fathers, games that made their arms strong and their hearts brave.

They called one of them Iceya, another Imfumba, and yet another Cumbelele.

Each game had a song, a lesson, and a spirit within it.

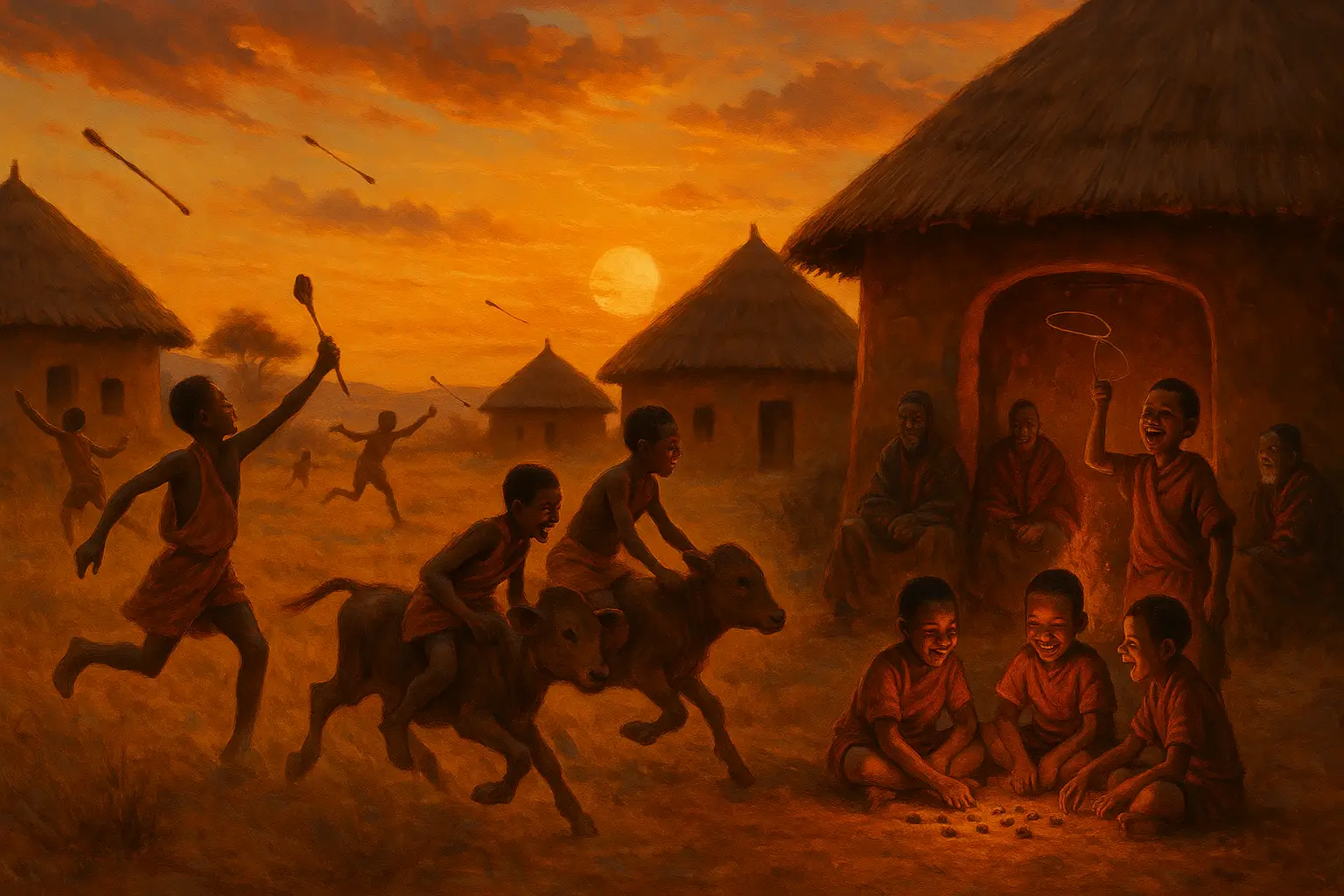

When the morning sun climbed the hills, the boys went to the fields with their knobbed sticks and little assagais. They threw them at ant-heaps and stones, and the air rang with their laughter and shouts.

“Tsi! ha! ha! ha! ha! Izikali zika Rarabe!” they cried when one of them struck the mark.

The weapons of Khakhabay!

They learned to throw straight, to strike hard, and to shout with pride.

The big boys ruled the small ones, as it has always been, and every day they grew stronger.

When the calves were grazing, the boys raced upon their backs, whistling commands, learning to guide and to follow. One of them always stayed behind to watch the herd, chosen by the drawing of grass stalks, one with a knot at the end. The boy who drew the knot became the herdsman.

He never complained, for he knew that his turn to play would come again.

When their legs were tired, the boys sat beside the river and made cattle from clay. They moulded oxen and calves, each with its own name. Some made puzzles with string and thongs, twisting and tying them in ways that only clever fingers could undo.

Others became tricksters, masters of illusion. They would hide a grain of maize in one hand, and though your eyes swore it was there, when they opened the hand it was gone now behind your ear, now in the dust.

The elders would shake their heads and laugh, saying, “That one will be another Hlakanyana, the little deceiver.”

When night fell, the fires burned low, and the children gathered inside the hut to play Iceya.

They sat in a circle. Each one had a small toy a grain of corn, a pebble, or a bit of wood.

The one who began hid his toy in one hand and called out, “I am the Inhlangano!”

Another would answer, “I am the Ipambo!”

Then they stretched out their hands, quick as lightning, and opened them together.

If the toys met, the Inhlangano laughed and won.

If they missed, the Ipambo took the victory.

The game went round and round, faster and faster, until only two were left.

That part was called the Umnyadala, the winding up.

The winner was crowned “the wearer of the tiger-skin mantle,” and the others clapped and cheered.

Sometimes the laughter lasted until the rooster crowed.

The next day they played Imfumba, the game of hiding and seeking a grain of maize.

One would pass his hands around the circle, pretending to place the grain in the others’ palms.

Sometimes he did, sometimes he did not.

The chosen guesser would point: “It is with you!”

If he was wrong, everyone laughed until their sides hurt.

Then came Cumbelele, the game of the song.

Three or four children stacked their hands one on top of another, singing,

“Cumbelele, cumbelele, pang-alala!”

At the last word they pinched sharply, each catching the one above.

Their laughter echoed into the night.

And when the wind rose, the boys brought out their nodiwu, a flat piece of wood tied to a thong. They spun it in circles above their heads until it sang with a voice like a spirit in the hills.

The old women warned them, “Do not play with the nodiwu when the wind is sleeping! If you do, you will wake it, and the storm will come.”

The boys only grinned, because they loved the sound of the wind when it called them to play.

So you see, my children, our games were not only for joy. They taught skill, strength, patience, and wisdom.

In the laughter of the young, the ancestors still danced, and the spirits of the veld still smiled.

That is why, when the sun sets behind the mountains and the cattle come home, you can still hear the faint echo of their cries:

“Tsi! ha! ha! ha! ha! Izikali zika Rarabe!”

The weapons of Khakhabay still fly in the air.