Long, Long Ago…

Long, long ago, before iron and ink came to the land, when the drum spoke louder than the written word, the people of the Amaxhosa held their marriages with great dignity and joy. The hills echoed with songs, and the dust rose beneath the stamping of many feet — for a marriage was not just a union of two hearts, but a weaving together of families, clans, and spirits.

The whole of this sacred celebration was called umdudo, from the old word ukudada to dance by spinning up and down for the heart of the marriage was the dance. There were other dances, yes, but none so full of power and meaning as this one. The umdudo was learned from childhood, practiced beneath the moon, for to dance it well was a matter of pride.

Of Fathers, Cattle, and Choice

In those days, a young woman did not choose her husband with her own tongue. Her father, or the one who guarded her, made the choice. Yet, the heart is its own drum, and sometimes love spoke first. When such a thing happened, when two hearts found each other before their elders spoke, they sometimes fled together into the night. Then, the families would follow, speaking, bargaining, until peace and cattle made all right again.

But not all hearts were free. Some girls were given to men older than their fathers, men who already had many wives. It was not the way of love, but it was the way of the world then.

Still, the woman was not without power. For what made a marriage truly binding was not words or dances but the cattle, the lobola. When the cattle were sent from the man’s family to the woman’s father, the union was sealed. Without them, no one called her a wife, and her children were not counted among the rightful.

This custom, though born of trade, was her protection. For if her husband struck her cruelly, her family could take her home and keep the cattle a heavy price for any man. Those cattle were shared among her father’s kin, and so she was never alone. Many eyes watched over her, and many hands guarded her children’s names.

The Family Names and the Blood Lines

There was one law the people held without question: no marriage could join those of the same family title. Blood might not flow between such people, even if their clans were far apart. A man of the Amanywabe, for instance, could not marry a woman whose father bore that same name not among the Xhosa, not among the Tembu, the Pondo, nor the Zulu.

Yet, such names bound the tribes in unseen ways. Those who shared a family title shared the same customs — at birth, in death, in the making of beer, and the songs sung over a newborn child. Though they might never have seen each other’s faces, they were bound by the same ancestral rhythm.

The Proposal and the Spear

When a man desired a woman, or when his father sought a bride for him, word was sent with a messenger. Sometimes he went with cattle a sign of seriousness and sometimes with only words. If the girl’s family accepted the proposal, they sent back an assagai, a slender spear. That spear spoke more clearly than any tongue: yes.

If they refused, the spear was returned, its silence sharper than its edge. But when it stayed oh, then the drums began to whisper of feasting to come.

The Journey of the Bride

When all was settled, and the families agreed, the girl was made ready to leave her father’s kraal. The time was chosen carefully she must arrive at her husband’s home after the sun had gone down, for darkness hides the face of transition and keeps evil spirits away.

A procession set out from her father’s home her kin, her friends, the young people of the village singing as they walked. With them came two animals: the Inqakwe, a cow given to bless her marriage and bring fortune, and an ox, a gift for the feast to be held at the husband’s kraal.

When they reached the place, the ox was slaughtered at dawn. Part of it was taken back by her people, and the rest was left for her new family. Messengers ran to call the neighbors, and as the sun rose, the air filled with music. The umdudo began.

The Dance of Union

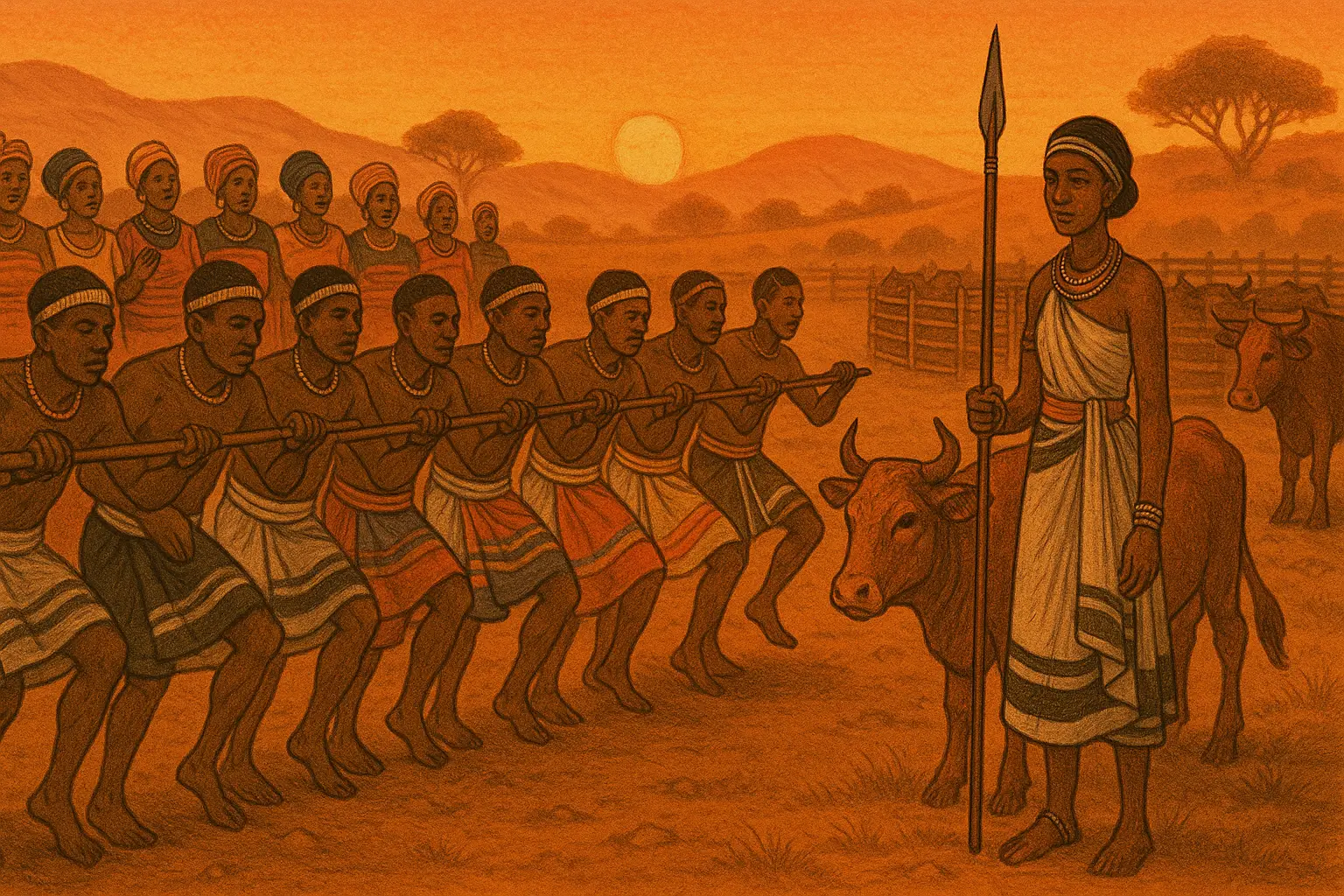

The men stood in straight lines, three or four deep, bare-chested and proud, their arms locked together. Behind them, in their own rows, stood the women he singers, the breath of the song. Between them lay an open space, sacred and waiting.

A man chosen for his voice began to sing, slow and deep. Others joined, the sound rising like thunder before the rain. At a certain note, all the men leapt straight into the air and came down with a trembling of their bodies, stamping the dust in rhythm with the earth’s own heartbeat. The women sang on, their voices high and strong, the song repeating in steady waves.

This was umdudo. It was the breath of life joining two homes. The dancing and feasting went on until the cattle were gone one day for a poor man, a full week for one whose herds were many.

The Closing of the Feast

When the final day came, the bridegroom and his friends came from one hut, the bride and her party from another. They met before the cattle kraal, the heart of the homestead. There, in the dust before all eyes, the bride lifted the assagai and threw it into the kraal, where it stuck upright in the ground.

That was the last act the sealing of the bond. The people began to leave, singing as they went, each man taking home his milk-sack. Once, in the old days, they would end with races of oxen but those times were fading, like smoke carried away by wind.

And so, the bride took her place among her husband’s people. Her Inqakwe cow was cared for as a symbol of her fortune. Her heart might be heavy with the weight of change, but she was now a wife, a bearer of lineage, and her story became part of the land’s great story the story of the Amaxhosa.